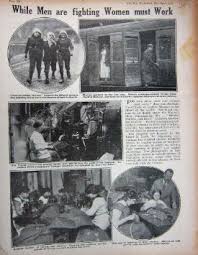

Railways at War 'WW1'

Policewomen on the railways http://www.btp.police.uk/about_us/our_history/policewomen_on_the_railways.aspx#sthash.IDn1KmxV.dpuf

We were the first police force in Britain to recruit women to our ranks. They joined in their numbers during the First and Second World Wars.

In the late 19th century, detectives at London terminals often took their wives on patrol with them, as a married couple wandering around a station looked less conspicuous than two men. These women were unpaid, and were often called to give evidence in court.

In the early 1900s, women had a different impact on the railways as the suffragette movement gathered pace. Bombs were left at many stations and others were burned down.

Women in the war

The First Great War took a huge toll on the young, male, railway workforce. Women were recruited to fill vacant jobs; the post office, bus companies and the railways being pioneers in the employment of women.

Shortly after the war began, Margaret Damer Dawson, a wealthy philanthropist, was waiting at a London station when she saw men attempting to recruit young Belgian girls as prostitutes. In response, she formed the Women’s Voluntary Service, a group providing policing services in London and other locations.

The first WPCs

The Great Eastern Railway recruited at least six women police officers, one of them as a sergeant. Thirteen worked on London's underground and there were also some in the Great Central Railway Police and the North East Railway Police. Unlike the Women's Voluntary Service, these women were employed as police officers and were sworn in as constables. This could make them Britain’s first officially employed policewomen.

The first four NER Policewomen were sworn in on 20th December 1917 and by August 1918 their number had increased to seventeen, led by Sergeant M Roberts at York.

They wore ankle length skirts and tunics with collar and tie. Each had a wide rimmed hat and a whistle and wore their duty bands on their left wrist.

Exact numbers and duties of railway policewomen are unknown. It is likely they provided a full range of policing services and were thought to be particularly useful in dealing with female offenders and victims. They could go in to ladies toilets and waiting rooms and could obtain statements from victims in women's hospital wards where men were not allowed.

Their powers varied. Records show the WPC on the Caledonian Railway had no police powers, while the sergeant at London’s Liverpool Street successfully detected female pickpockets and policewomen on the Metropolitan Railway were tasked with preventing soliciting at Piccadilly Circus.

Between the wars the numbers of policewomen declined although their services were still needed in some areas; on 29 May 1924, Ada Atherton was recruited as a 'female detective' at Waterloo station, the first recorded woman detective. She went on to complete over 25 years of police service.

The Second World War again saw an influx of women to the railway. Policewomen were stationed across Britain and our force archives have details of over 100 paid Women Special Constables.

One woman gained publicity in tragic circumstances; on 6 January 1944 WPC Lillian Gale was run over and killed by an engine in Plymouth GWR docks.

compiled by Tony Allen

The first British ambulance trains, which operated on the Western Front, consisted simply of a few empty French goods wagons with straw laid on the floor. At the end of August 1914, the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) were given three locomotives and a further number of goods wagons and a few carriages. They were converted and divided into three ‘trains’. Each consisted of wards, surgical dressing rooms and dispensaries and were designated British Ambulance Trains 1, 2 and 3 respectively. The RAMC continued converting French rolling stock up to train number 11, and in November 1914, the first specially built medical train was sent out from the UK and designated number 12. No train was given the number 13 and near the end of the war, number 43 arrived in France. As with the ambulance cars, several of the trains were built with voluntary contributions. For example, number 12 was Lord Michelham’s, No. 15 was Princess Christian’s and the United Kingdom Flour Millers donated No. 16.

This card depicts a scene early in the war, when French goods wagons were used to transport the wounded. Captioned “R.A.M.C. ENTRAINING WOUNDED FOR HOSPITAL”, the picture was painted by Harry Payne. It was one of a set of six “Oilette” cards (series 8821) showing the RAMC at work. Text on the back of the card reads: “The completeness and efficiency of the splendid work of the Royal Army Medical Corps demands and deserves a volume of appreciation. From the firing line to the hospital, from thence to the base. In the train, the Hospital Ship, and at home, everything that can sooth the suffers or heal their wounds, every agency, personal or material for this ameliorative work, is lavishly provided.”

| As mentioned above, the first specially equipped ambulance train was sent out from the UK in November 1914, this card depicted one of them. "A CASE FOR “BLIGHTY”’. The two female nurses depicted on this "CANADIAN OFFICIAL" card, were members of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service - known affectionately as QA's. When war broke out in August 1914, there were just under 300 QA's serving with the British Army, but by the end of the year the number had risen to 2,223 and when the war ended over 10,400 trained nurses had enrolled in the service. The QA's were distinguishable from other nurses by the short scarlet capes they wore. |

The publisher of this card is not named. It shows "...two beds arranged for sitting up cases" and was known as a "Continental Ambulance Train" It was built at the GWR Works in Swindon in 1915. Between August 1914 and December 1918, over 5,000,000 patients were carried by these trains on the Western Front.

Another interior view of a carriage on an ambulance train. This was a 'Ward Car' built by the Caledonian Railway Company and although there are no details of printer or publisher on the back of the card, it was probably released by the company.

Ambulance Trains in the UK

Early in the conflict, a group of regional railway companies donated 12 ambulance trains to the army medical services and very soon, they were carrying patients from Southampton to different parts of the U.K. As the home bound casualties mounted, four emergency trains made up of corridor coaches and dining cars came into service to accommodate ‘sitting’ patients. In addition, a number of North-Eastern Railway Company vans were fitted out for ambulance use and coupled to ordinary passenger trains. These special vans transported the wounded that had been landed on the northeast coast bound for hospitals at Selby and York.

The wounded from the Western Front and elsewhere, were carried by hospital ship to the UK and while still at sea, the ship would cable information ahead of the various categories of patients they had on-board and their estimated time of arrival at port. Each patient was labelled with details of his wound; another label was marked with one of five areas in Britain nearest his home. If a man was seriously injured a plain red label was also attached to him, indicating that he required ‘special consideration.’ Before disembarkation began, huge ‘reception sheds on the quayside were lit and heated’. Beyond the sheds the ambulance trains waited.

The role of ambulance trains in the United Kingdom was different from that of medical trains on the Western Front. There, patients were entrained from medical units scattered over a large area where their wounds had only received emergency treatment. On the train to the base, they received proper medical attention. This continued at the base hospital and in the hospital ships that carried them home. Consequently, when they arrived at home ports most casualties were already in a reasonably stable condition.